At the quarter century mark, The New York Times polled a mysterious cabal of cinephiles, created a fancy website, and presented their “100 Best Movies of the 21st Century” list to much fanfare. Best-of listicles are such great clickbait (I’m certainly not immune) and best film lists are fun to debate and generally throw things at. In this case, 19 films on their list overlap with my 100 Best Films of the 21st Century list—theirs more mainstream and maybe not as weird, but mainly (no knock on the ones they included—most of them, anyway) just missing most of the best films made this century.

I won’t highlight omissions, as there are 81 of them. Wait, I lied. How could you possibly omit Zama or Caché or…it’s truly unimaginable.

Metrics for the New York Times’ 100 Best Films List (with Comps to Mine)

A few metrics that highlight the differences in our two lists: only 33% of the films on the NYT’s 100 Best Films of the 21st Century list are primarily non-English language films1 (compared to approximately 70% on my best films of the century list), and while nearly 75% of the movies on their list grossed over $10M, only approximately 40% on mine reached that mark2.

While one might look at these figures and very reasonably point to ethnocentrism and bandwagon bias (largely driven by commercialism—marketing, ubiquity, etc—the NYT’s list also features 41 Best Picture Oscar nominees3, vs 17 on my list) as factors influencing these differences (and, as well, what those differences might say about the NYT’s list in particular), others might point out my list’s lean toward the odd (“you’re just into obscure stuff, dude”4), but this is, to me, at least, an unconvincing rationale.

The truth is, even at roughly 70%, my list is undoubtedly light on non-English language films—I’ll explore more and that number will no doubt grow. Living in an American streaming ecosystem may represent a challenging path toward international film discovery, but it does not mean that the privileged few poll respondents selected by NYT editors5 are excused for not more thoroughly plumbing the cultural landscape (/high horse).

And then there’s the question of taste and sophistication. I’ll stop here before I throw up on myself.

Polling Scope and Skewed Results

In the NYT list’s marginalia, they mentioned allowing respondents “to submit up to 10” (unranked) choices. Why they didn’t allow up to 100 choices is an open question (as is why they disallowed ballot ranking), but researchers may have wanted to:

- Limit non-response bias—respondents dismissing or putting off the ask and, in the end, supplying nothing.

- Avoid “satisficing,” where respondents might provide “good enough” answers instead of optimal ones to finish the task quickly. After all, recalling 25 years worth of film watching, summoning sufficient subjective criteria to rank them, and then ranking them relative to one another represents a relatively high cognitive load.

- Prioritize what they might consider to be “high-confidence data“—answers that reflect intensity of preference vs choices that might be the result of cognitive fatigue or, as mentioned above, carelessness.

- Limit the amount of relative influence any single 100 film-providing respondent would have over those supplying, say, 5-10 (whether out of busyness, poor recall, laziness, or indifference).

However, operating this way, the same researchers ran the risk of censoring data—resulting in film choices (eg., choices 11-100) that, because respondents are limited to 10, are ultimately hidden. Another way of putting this is data loss, with the NYT’s 100 best film list less accurate because it excludes respondents’ secondary preferences.

The team at the NYT is a smart one (they leveraged The Upshot—a department “focused on data and analytical journalism” to design this study), and they had some study design tradeoffs on their hands. Also in the list’s marginalia is a concession that “some submitted fewer” than 10 choices. This is particularly telling—that a percentage of respondents couldn’t be bothered to provide 10 films, indicating that even their efforts to reduce non-response bias by limiting responses to 10 choices did not ensure 10 choices (and they did not say how many blew them off entirely)6.

People (including Hollywood “stars” and other highly-influential contacts in the NYT’s Rolodex) are busy, yes, but also distracted, and many might—even though being asked to participate in such a poll by the NYT is clearly a privilege—devalue the process of actually coming up with their own personal list of 10 best films (let alone 100) when there’s so much lifemaxxing, looksmaxxing, and bed rotting to do7. I mean, there are only so many hours in a day.

By narrowing the scope of the study, the researchers took a step to ensure—or, at least, encourage—participation, but they simultaneously sacrificed depth for feasibility. I’d be willing to bet that there was some internal hand-wringing over this decision. How can you justify ending up with a list without a single film by Lucrecia Martel, Claire Denis, Peter Strickland, Marie Kreutzer, Guy Maddin, Chantal Akerman, and a number of other unrepresented contemporary masters of the form?

Taste (see—it’s back) is one answer, which can be represented by omission and also the space-taking inclusion of other films (including so many commercial choices that I won’t detail specifically) by less discerning respondents, but another answer is the aforementioned data loss, where the films of those directors maybe don’t make it into many respondents’ top 10 lists (tragically, I know), but they are nevertheless represented in respondents’ mental lists—only further down, past number 10, where, at least in data collection for this poll, they’re censored and therefore hidden to the team at The Upshot. This is unfortunate, as it leaves us with a “100 best” product that, with its gaping blind spot, functions more as clunky conversation starter and curious cultural artifact than worthwhile, representative, integritous study.

Final Notes

On a minor note, there are two or three films on the NYT list, like The Lives of Others and Volver, that I haven’t yet gotten around to seeing, so the number of overlaps might get a micro bump at some point—a minor détente scheduled for some unknown future date. I should mention, btw, that I maintain a list of the 500 Best Films of All Time. Feel free to email with any comments. Without further ado…

The New York Times’ List of the 100 Best Movies of the 21st Century

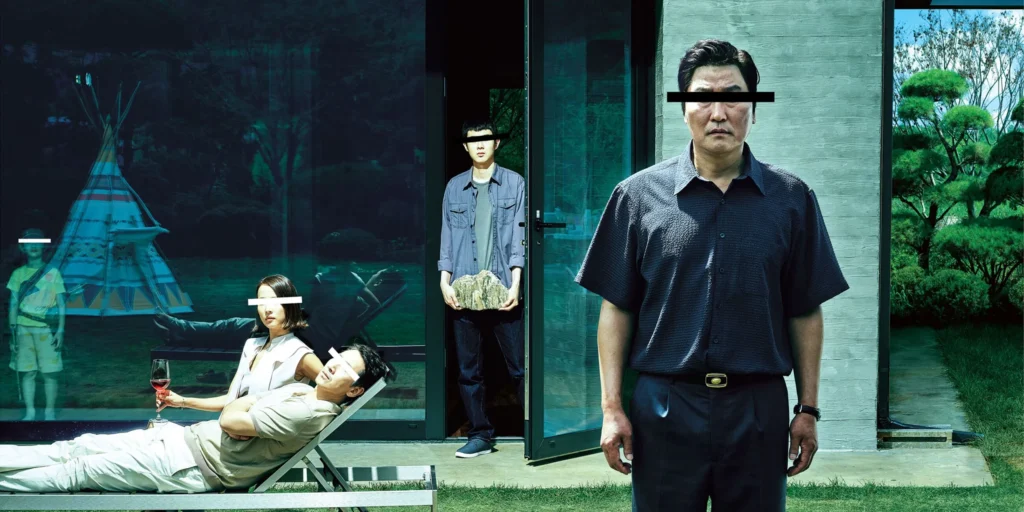

- Parasite (Bong Joon Ho, 2019)

- Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001)

- There Will Be Blood (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2007)

- In the Mood For Love (Wong Kar Wai, 2000)

- Moonlight (Barry Jenkins, 2016)

- No Country For Old Men (Joel & Ethan Coen, 2007)

- Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Michel Gondry, 2004)

- Get Out (Jordan Peele, 2017)

- Spirited Away (Hayao Miyazaki, 2001)

- The Social Network (David Fincher, 2010)

- Mad Max: Fury Road (George Miller, 2015)

- The Zone of Interest (Jonathan Glazer, 2023)

- Children of Men (Alfonso Cuarón, 2006)

- Inglourious Basterds (Quentin Tarantino, 2009)

- City of God (Fernando Meirelles, 2002)

- Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Ang Lee, 2000)

- Brokeback Mountain (Ang Lee, 2005)

- Y Tu Mama Tambien (Alfonso Cuarón, 2001)

- Zodiac (David Fincher, 2007)

- The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin Scorsese, 2013)

- The Royal Tenenbaums (Wes Anderson, 2001)

- The Grand Budapest Hotel (Wes Anderson, 2014)

- Boyhood (Richard Linklater, 2014)

- Her (Spike Jonze, 2013)

- Phantom Thread (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2017)

- Anatomy of a Fall (Justine Triet, 2023)

- Adaptation (Spike Jonze, 2002)

- The Dark Knight (Christopher Nolan, 2008)

- Arrival (Denis Villeneuve, 2016)

- Lost in Translation (Sofia Coppola, 2003)

- The Departed (Martin Scorsese, 2006)

- Bridesmaids (Paul Feig, 2011)

- A Separation (Asghar Farhadi, 2011)

- WALL-E (Andrew Stanton, 2008)

- A Prophet (Jacques Audiard, 2009)

- A Serious Man (Joel & Ethan Coen, 2009)

- Call Me By Your Name (Luca Guadagnino, 2017)

- Portrait of A Lady on Fire (Céline Sciamma, 2019)

- Lady Bird (Greta Gerwig, 2017)

- Yi Yi (Edward Yang, 2000)

- Amelie (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 2001)

- The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2012)

- Oldboy (Park Chan-wook, 2003)

- Once Upon A Time in Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino, 2019)

- Moneyball (Bennett Miller, 2011)

- ROMA (Alfonso Cuarón, 2018)

- Almost Famous (Cameron Crowe, 2000)

- The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, 2006)

- Before Sunset (Richard Linklater, 2004)

- Up! (Pete Docter, 2009)

- 12 Years A Slave (Steve McQueen, 2013)

- The Favourite (Yorgos Lanthimos, 2018)

- Borat (Larry Charles, 2006)

- Pan’s Labyrinth (Guillermo del Toro, 2006)

- Inception (Christopher Nolan, 2010)

- Punch-Drunk Love (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2002)

- Best in Show (Christopher Guest, 2000)

- Uncut Gems (Josh & Benny Safdie, 2019)

- Toni Erdmann (Maren Ade, 2016)

- Whiplash (Damien Chazelle, 2014)

- Kill Bill Vol. 1 (Quentin Tarantino, 2003)

- Memento (Christopher Nolan, 2000)

- Little Miss Sunshine (Dayton & Faris, 2006)

- Gone Girl (David Fincher, 2014)

- Oppenheimer (Christopher Nolan, 2023)

- Spotlight (Tom McCarthy, 2015)

- TAR (Todd Field, 2022)

- The Hurt Locker (Kathryn Bigelow, 2008)

- Under The Skin (Jonathan Glazer, 2013)

- Let The Right One In (Tomas Alfredson, 2008)

- Ocean’s Eleven (Steven Soderbergh, 2001)

- Carol (Todd Haynes, 2015)

- Ratatouille (Brad Bird, 2007)

- The Florida Project (Sean Baker, 2017)

- Amour (Michael Haneke, 2012)

- O Brother, Where Art Thou (Joel & Ethan Coen, 2000)

- Everything Everywhere All At Once (The Daniels, 2022)

- Aftersun (Charlotte Wells, 2022)

- Tree of Life (Terrence Malick, 2011)

- Volver (Pedro Almodóvar, 2006)

- Black Swan (Darren Aronofsky, 2010)

- The Act of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer, 2012)

- Inside Llewyn Davis (Joel & Ethan Coen, 2013)

- Melancholia (Lars von Trier, 2011)

- Anchorman (Adam McKay, 2004)

- Past Lives (Celine Song, 2023)

- The Fellowship of the Ring (Peter Jackson, 2001)

- The Gleaners and I (Agnès Varda, 2000)

- Interstellar (Christopher Nolan, 2014)

- Frances Ha (Noah Baumbach, 2012)

- Fish Tank (Andrea Arnold, 2009)

- Gladiator (Ridley Scott, 2000)

- Michael Clayton (Tony Gilroy, 2007)

- Minority Report (Steven Spielberg, 2002)

- The Worst Person in the World (Joachim Trier, 2021)

- Black Panther (Ryan Coogler, 2018)

- Gravity (Alfonso Cuarón, 2013)

- Grizzly Man (Werner Herzog, 2005)

- Memories of A Murder (Bong Joon-ho, 2003)

- Superbad (Greg Mottola, 2007)

Footnotes:

1 Films from the NYT’s list that are non-English language or primarily non-English language: Parasite, In the Mood For Love, Spirited Away, City of God, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Y Tu Mama Tambien, A Separation, A Prophet, Portrait of A Lady on Fire, Yi Yi, Amelie, Oldboy, ROMA, The Lives of Others, Pan’s Labyrinth, Toni Erdmann, Let The Right One In, Amour, Volver, The Act of Killing, Memories of A Murder, The Worst Person in the World, Anatomy of a Fall, The Zone of Interest, The Gleaners and I. Only the Oscar winning films are mentioned in the list’s Wikipedia entry.

2 Revenue reference sources: Box Office Mojo and The Numbers.

3 Films from the NYT’s list that received Oscar Best Picture nominations: Parasite, There Will Be Blood, Moonlight, No Country For Old Men, Get Out, The Social Network, Mad Max: Fury Road, The Zone of Interest, Inglourious Basterds, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Brokeback Mountain, The Wolf of Wall Street, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Boyhood, Her, Phantom Thread, Anatomy of a Fall, Arrival, Lost in Translation, The Departed, A Serious Man, Call Me By Your Name, Lady Bird, Once Upon A Time in Hollywood, Moneyball, ROMA, Before Sunset, Up!, 12 Years A Slave, The Favourite, Pan’s Labyrinth, Inception, Whiplash, Little Miss Sunshine, Oppenheimer, Spotlight, TAR, The Hurt Locker, Carol, Amour, Everything Everywhere All At Once, Aftersun, Tree of Life, Black Swan, Past Lives, The Fellowship of the Ring, Gladiator, Michael Clayton, The Worst Person in the World, Black Panther, Gravity.

4 All but one of the films on my list (Nina Menkes’ Phantom Love) had a US theatrical release—a criteria for ballot inclusion in the NYT poll. Still, this mandate is a load of crap and all counterarguments are fundamentally lacking in merit. Let’s stop gatekeeping and reflexively copping outdated approaches from gamed promotional schemes like the Oscars.

5 The NYT listed some of the “hundreds of directors, actors, cinematographers and others in and around the film industry” chosen, along with their unranked film selections, and in her Reddit AMA on the topic, NYT writer Leah Greenblatt added that “what we knew we didn’t want in the mix, and wouldn’t include here, was traditional film critics”—a solution to a problem that maybe didn’t need solving.

6 The NYT researchers also mentioned that “voters were given the option to pick which of two randomly selected films was better in a series of matchups” and that this data was somehow used in their final ranking calculations—possibly by “taste-grading” respondents on the basis of their answers to the follow-up poll and then weighting respondent rankings accordingly (NYT writer Leah Greenblatt intimated as much in her Reddit AMA, saying this mechanism “helped to weight the final results by giving us a fuller picture of how people felt about a whole range of films on the list beyond just the ten they voted for”). The researchers did not disclose how many respondents participated in this follow-up, quality control measure.

7 In her Reddit AMA, NYT writer Leah Greenblatt referred to their hounding of Hollywood A-list respondents to actually respond as “sometimes like a treasure hunt and sometimes a wild goose chase.”